An apology to my teenage self

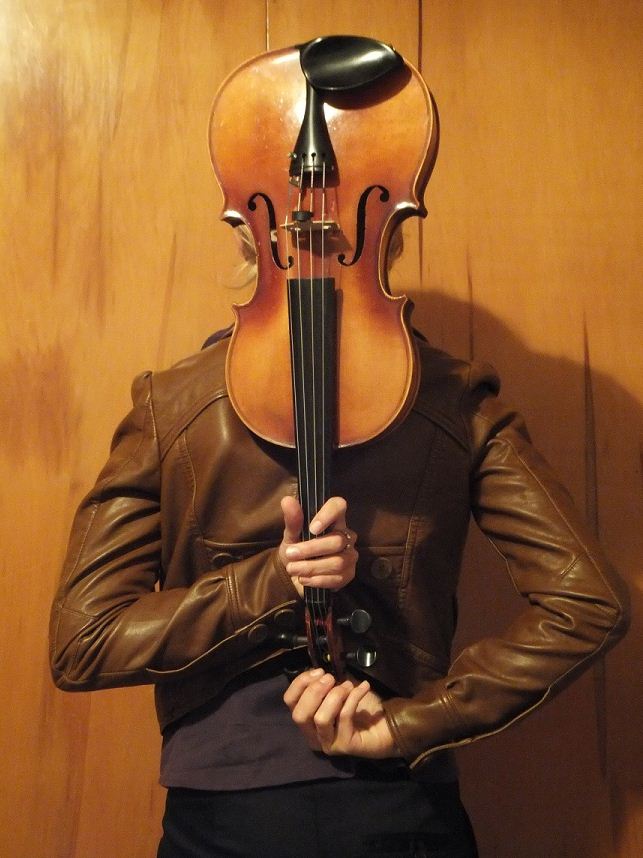

Mackenzie McCarty has sold her decades-old viola – and waved goodbye to a childhood dream.

On Sunday I sold my childhood dream for $850, shipping included. I zipped her tightly into a green cloth case beside memories and the faint sound of applause, and my viola did not protest. She remained silent – much as she has for the past two years. This silence, in fact, is what drove me to sell her in the end. A silent instrument is like a silent child: sad and strange.

I was 11 when I first began to play. The nice lady with fly-away hair in the enrolment office told me it was orchestra or PE. Having never been the touch football type, I embraced my cheap, cherry-wood set of strings with outstretched fingers and all the earnest enthusiasm of childhood.

At 14 I made it into our high school’s elite chamber orchestra, and two years later we played at Carnegie Hall. I can still remember the euphoria that rippled through the sinews in my fingertips, spinning like an electric spider along my spine during our final, perfect note.

By the time I was 16, people paid to see me play. Our orchestra performed to packed houses of 1500 people in razzle-dazzle cocktail dresses and carefully pressed trousers. My little pubescent world unfolded to a constant backdrop of Vivaldi, Brahms and Mozart. The bruise which often arose beneath my chin was a proud sign of my dedication, and I encouraged it by pressing my chinrest deep into my jaw as I played.

My first kiss was tied to music. In a fit of romantic idiocy, I stashed my beautiful new viola – a Christmas present from my mother only weeks before – in a grove of trees beside a public walkway whilst my beau and I frolicked on a nearby beach. When we returned, it had been stolen. My mother was not impressed, and I spent the better part of a year paying her back.

My adult briefcase, I then imagined, would contain a spare set of strings and a disorganized stash of sheet music. Perhaps I would get the fingers on my left hand insured. I would run from practice to endless concert halls in long, black dresses, red lipstick and comfortable shoes. When I grew old, I would retire and teach children how to play.

I can’t remember the moment when I realized this would never come true. All I know is that I boarded a plane to Auckland some months after graduating high school, and my desire to perform somehow got left behind. For the first two years, I tried hard to pretend that this was just a phase. I played in the university orchestra, and hated it.

My fingers grew stiff, and the rush of being on stage wilted into discomfort. All around me were music students destined for the future I had once held in my hand and had lost hold of. I could swear my viola looked at me with pity, and perhaps a wash of disdain.

So I have sold her. She is 70 years old, a grandmother, and I can no longer stand her disappointment. It is said that the sound of a string instrument deteriorates if it is not played, and I couldn’t bear to be the one responsible for the loss of this aging madam’s dignity. German-crafted, she has survived the Second World War, a journey across the world, and the steady decline in the appreciation of her musical genre. If cherished, she will survive me – a vessel containing all the glittering dreams of my teenage self. I will miss her.