Younger generation losing te reo Māori

Te reo Māori is decreasing in the age group vital in keeping the language alive

Fewer young Māori are speaking te reo – fuelling fears for the language’s survival.

The number of te reo Māori speakers in the generation vital to keeping the language alive has fallen in the seven years between Census counts.

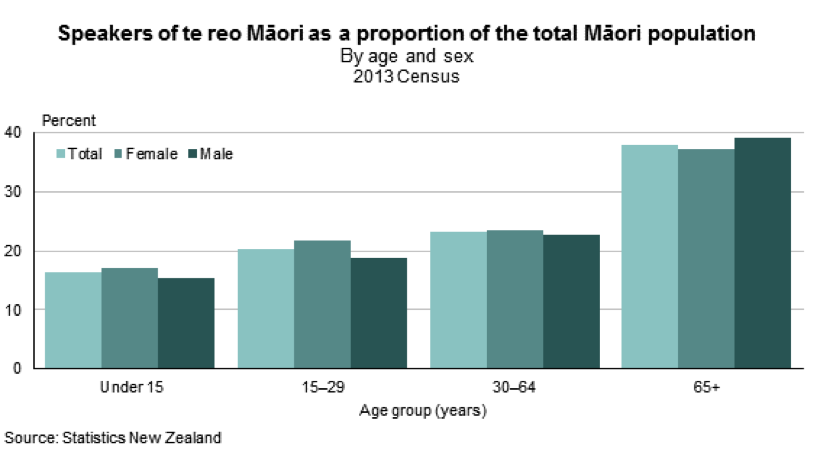

According to Statistics NZ the December 2013 Census, revealed 23.3 percent of Māori aged 15 to 29 can hold a conversation in te reo Māori.

This is an 8.2 percent decrease from the 2006 Census.

The older generation remain the flag bearers for the language, the Census revealed.

The age group 65 years and over increased the number of te reo speakers from 9.8 percent to 11 percent.

Statistics New Zealand measured te reo Māori through another data source called Te Kupenga, which asked about general and cultural well-being, with more detailed questions on language proficiency for Māori.

While the 2013 Census measured te reo speakers by their “ability to hold a conversation,” Te Kupenga asks more in-depth questions as around the ability to speak, listen, read, and write in te reo Māori, and the environments in which Māori used the language.

Between the ages of 15 to 24, 132,000 people classed themselves as Māori but out of that total just 11,000 answered affirmatively when asked whether they knew the language “very well/well”.

An additional 60,500 know more than a few words or phrases.

Chloetilde Pomare is one person trying to recapture the language of her culture.

The 23-year-old, with Māori and Fijian heritage, recently completed a Diploma in te reo Māori through Waiariki.

Growing up she attended many Māori schools such as Kohanga as a toddler, Te Kura Kaupapa Māori o Te Hiringa for Primary, and a year at Hato Petera College.

But she then went through mainstream intermediate and high school, and tertiary education.

“My Fijian mother who was born in New Zealand didn’t have the opportunity to learn her culture at a young age, so she decided to send her children to Kohanga because she believed it was a privilege to know your culture.”

Although Pomare says she has lived a more European lifestyle, she saw the diploma in te reo Māori as a good opportunity to regain some confidence in her reo.

Pomare said she would definitely look at passing the language on to her children.

“It has moulded the person I am today and I am very proud to have been brought up the way that I have. If I could do something different from my own childhood it would be to speak te reo to them [my children] at home.”

Today there is an array of learning opportunities available.

Te Wananga O Aotearoa and the Waiariki Institute offer te reo Māori in levels ranging from a certificate to a degree, with some courses free. The Waikato University and Wintec also offer te reo Māori courses.

Te Wananga O Aotearoa, Te Rapa campus tutor, Mere Wakama, teaches a free te reo Māori in a level 2 certificate.

She has been in her role for four years, and says numbers have grown yearly.

“So when I first started there were only two classes with 18-20 people, then next year 25-28 people. And then last year we had three classes of up to 25 people, and then this year there are five classes with 20-25 people.”

In terms of target age groups Wakama said the courses had a 50/50 split with a good mix of younger and older Māori learning te reo.

“The oldest person is our class is 70… and the youngest is 17.”

Wakama said she tries to target younger Māori.

“We have to market our own programmes and find our own students, so my market has been a younger generation through Facebook friends and word of mouth.”

Wakama said the younger Māori generation in her course said they decided to take the course because they were not taught the language growing up, or at school.

New Zealand Statistics note that the Māori ethnic group is made up of people who stated in the census that Māori was their only ethnic group, or one of several ethnic groups.