Scientist surprised by low level of NZ shark attacks

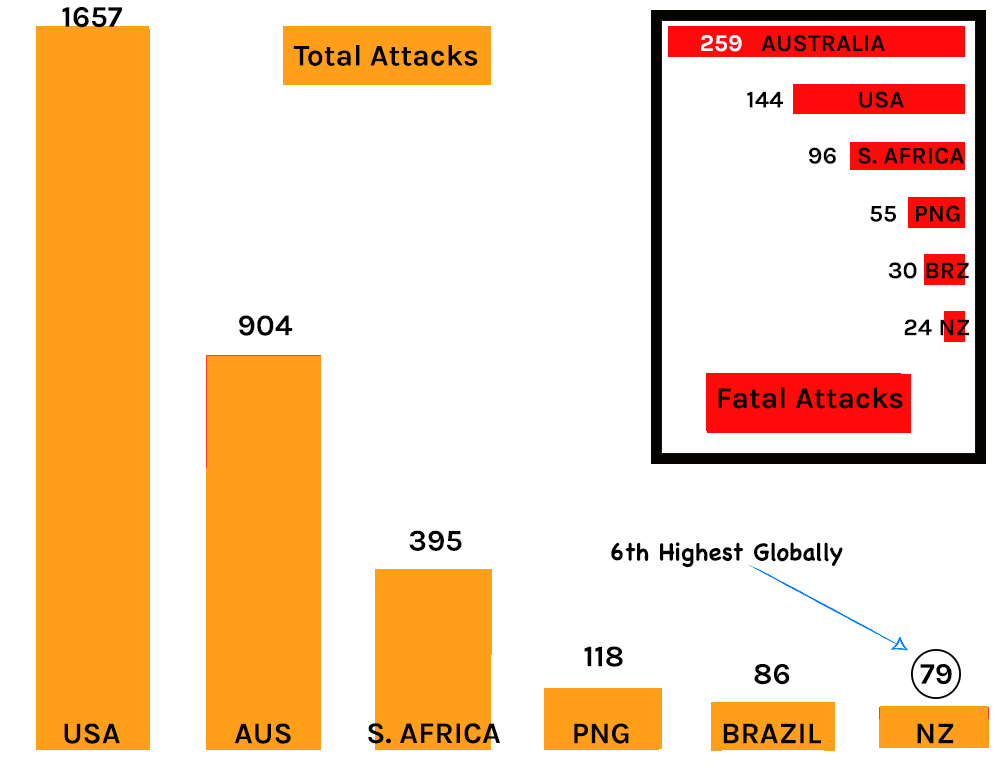

NZ rates 6th in the world for unprovoked great white shark attacks. What are your chances next time you go for a dip?

Will Kiwis need to rethink their recreational use of the sea if shark attacks continue to increase in our waters?

Shark attacks in New Zealand as reported to the Global Shark Attack File (GSAF) increased more than 60 percent, comparing the decades 1990-2000 and 2000-2010.

In the last six calendar years (2011-2016) there have been seven unprovoked shark attacks in New Zealand, with one of these – the attack on Adam Strange at Muriwai in 2013 – being fatal.

“I think the surprising thing is not that people get bitten, but how rarely they get bitten,” says Dr Malcolm Francis, NIWA scientist and New Zealand’s foremost shark researcher.

“We seem to be pretty lucky in that we’ve got great white sharks right around New Zealand, but they must be pretty good at distinguishing people from their normal food, otherwise there’d be people getting eaten every week.”

What are the Odds?

New Zealanders have a greater chance of being struck by lightning than of being attacked by a shark, and a greater chance of winning Lotto.

“The odds [of shark attack] are just ridiculous,” says Darren Mills, New Zealand’s most recent great white shark attack victim, and creator of Burn Less Wood stovetop fans.

“Probably more chance of getting in a car accident than you have of getting bitten by a shark. But then, that’s what I always said in the back of my head.”

Mills, who had been surfing in New Zealand waters several times each month for about eight years, was aware of the risk, but said he did not think about it much.

“You only think about it when you’re waiting out back [beyond the surf] sometimes, when you see the odd shadow which might be weed or a dolphin. You just never think it’s going to happen to you, you know?”

Mills was surfing off the Catlins in February 2014 when the great white attacked him. He was hit while lying on his board. The shark bit up into the board and down into Mills’ leg. A Department of Conservation scientist later analysed the bite and confirmed it was likely to have been a great white, Mills said.

“After I got attacked, I would have put a bet on of someone else getting attacked down south by another great white. I would have put a bet on for it happening within another year or two,” he said.

To date, there have been no more great white attacks in New Zealand waters. Mills has not been surfing since his attack.

Friend or Foe?

Mills wasn’t the only one expecting more shark attacks in the two years following his ordeal.

The following year, 2015, broke the record for the highest number of attacks globally, prompting director of the International Shark Attack File (ISAF) at the University of Florida, George Burgess, to predict 2016 was going to be worse. (It wasn’t).

However, some see a much greater threat. While scores of people are being attacked by sharks each year, people are still killing millions of sharks annually.

More than one third of shark species are now heading for extinction, says organiser and founder of Shark Attack Survivors for Shark Conservation, Debbie Salamone.

“Conservation of these animals is critical because they are vital to marine food webs that keep our oceans healthy. Everyone needs the oceans, and we need abundant sharks for healthy oceans,” she said.

Salamone is also a resident of Florida, which has the highest rate of unprovoked shark attacks in the US. A shark – likely a spinner or blacktip shark – bit her in 2004 off Cape Canaveral, severing her Achilles tendon and tearing her heel apart.

Salamone has been advocating for shark conservation since and believes people using the sea recreationally should be aware of the risks and take precautions.

“If I know sharks are migrating or gathering in a certain area, I don’t go in. That’s a personal choice. In those cases, I believe my desire to swim in the ocean is not as important as a shark’s need to live and thrive in its own ecosystem.

“I still go in the ocean, but I only go when the water is clear, so sharks can see me and not mistake me for a fish. Most bites, including mine, are cases of mistaken identity.”

Nonetheless, Mills said the water was so clear when he was attacked he could see corrugations in the sand at the bottom.

Kiwis beat Aussies (in complacency)

Francis thinks compared to the Australians, Kiwis are sometimes too complacent.

“We can get a bit complacent I suppose if there aren’t any attacks. We think they happen in Australia and aren’t so much a problem here. So we tend to get a little blasé about it.

“Other people who use the water all the time, particularly divers and spear fishermen, are well aware there are lots of sharks out there. But the risks are so low – extremely low – that most people don’t think about it when they go in the water.

“Sharks have always been an issue, but there are just more and more people getting in the water now, particularly in Australia,” he said.

There is a correlation between the rise in human population and the rise in the number of shark attacks around Australia. The yearly average for shark attack fatalities there is between one and two.

“If your average is one event a year, seven is not actually all that much higher if you’re thinking in statistical terms,” Francis said.

“When you’re talking about low frequency events, it’s still a very low number. If it was a sustained increase over a number of years, then you’d be wanting to look for an answer.”

The Australians, who have the highest rate of shark attack fatalities on the planet, have been looking for an answer. They held a shark expert conference in Sydney in September 2015 to brainstorm ways of reducing the risk of shark attacks.

Australian shark attacks increased by more than 75 percent in the first decade of the new millennium, leaping from an average of six and a half total incidents per year from 1990–2000, to 15 total incidents per year from 2000-2011, according to Australian Shark Attack File data.

Just When You Thought it was Safe?

Following five great white shark attacks in Dunedin between 1964 and 1973 – three of which were fatal – the country’s first ever shark nets were installed at St Clair and St Kilda beaches.

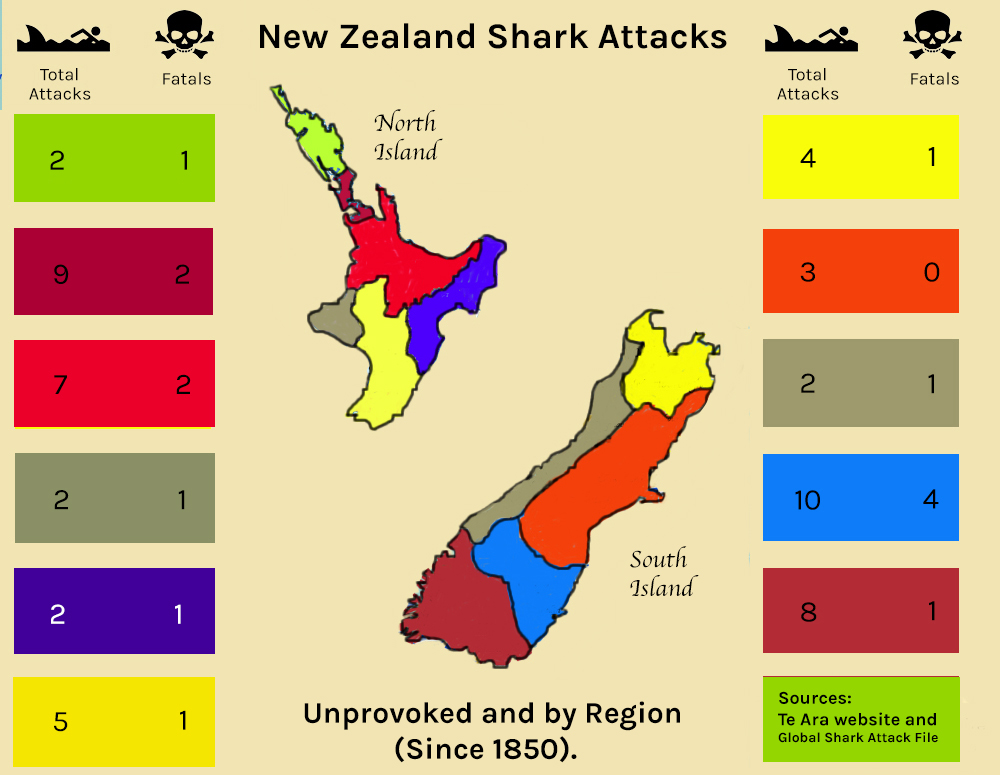

Otago has New Zealand’s highest recorded number of shark attacks to date: 10 attacks which include four fatalities. Southland (including Fiordland) is a close third with eight attacks including one fatality.

Francis – who audio and satellite tagged white sharks around Stewart Island – believes the reason for a greater number of recorded shark attacks in Otago and Southland is probably a combination of larger seal populations and reduced fishing pressure.

“We know from our tagging that sharks hanging around seal colonies around southern New Zealand hardly ever go deeper than 50 metres, so they’re patrolling in pretty shallow water, near shore,” he said.

The shark nets at St Clair and St Kilda were removed some 40 years after installation when their negative impact on other marine life was questioned along with the validity of their annual $38,000 cost for local council.

Surfers were warned to get out of the water at St Clair beach the following summer (2012) while a possible shark sighting was investigated.

“Going into the ocean comes with risk,” Salamone said. “You are entering a world where sharks are predators and you are no longer at the top of the food chain. The ocean is the sharks’ world and we need to respect that.”