Tokelauans in NZ: Saving an identity, miles from home

The story of Tokelau communities in NZ today…

Picture: Juliana Tagimamao Perez (Facebook)

Tokelau is not as well known to the world as are its Pacific neighbours,

Samoa and Cook Islands. It is but a dot on the world map, one you would have to

squint hard to see; a grain of sand surrounded by the blue of the Pacific.

It is made up of three atolls – Fakaofo, Nukunonu and Atafu – and is a 24-hour

boat ride 300km north of Samoa for anyone interested in visiting.

Made a New Zealand protectorate in 1925, Tokelau today hold New Zealand passports and use New Zealand dollars on the island.

In the years that followed protectorate status New Zealand-funded schemes

and scholarships would result in people leaving the island.

One of the biggest schemes was the Resettlement Scheme in the 1960’s that saw Tokelauans move to New Zealand as New Zealand government helped with overcrowding on island.

Other schemes saw Tokelau scholarship students go in search of education to help develop the island life.

But hopes of developing the atolls with the return of scholarship

students soon diminished as most scholars chose to live

permanently overseas.

Most had married, some with people of other nationalities and, soon, turned what was initially supposed to be temporary locations into their new home countries.

Over the years more families have trickled out of the atolls seeking the opportunities other

countries had to offer.

They left behind the familiar narrow roads and vast lagoons and migrated to the big cities in the hopes that it would give their children a better lifestyle.

But, even so far from home, Tokelauans in New Zealand have preserved the close-knit community bond by holding events where they come together to celebrate the Tokelau culture.

Semo Koro, who lives in Auckland with his wife and three children, is President of Mafutaga Tupulaga Tokelau I Niu Hila; a committee responsible for the planning of Tokelauan events.

These events are usually set during special occasions such as the Tokelau Easter Festival, made up of sports and traditional fatele dancing competitions.

This year’s Easter Tournament was to be hosted by Tokelau Hutt Valley Sports in March and Tokelau communities from around New Zealand, as well as Melbourne planned to attend.

The excitement buzzing around the communities came to an abrupt end as the

growing number of COVID-19 cases forced borders to close and New Zealand went

into lockdown.

Mr Koro said that the government’s announcement to stop gatherings of

500 came two weeks before the tournament was set to take place.

And although they were devastated, they also knew it was the best decision to be safe.

“I felt sorry for the youth, we had been preparing for weeks, so much

time and effort went into the practices.”

Mr Koro was born in Samoa to a Samoan mother and Tokelauan father, they lived in Samoa most of his youth but his Tokelauan roots were not lost in his upbringing.

He remembers spending most Christmas holidays back in his father’s Atafu village.

Mr Koro recalls the high regard the Tokelau communities held for the

elders as they were seen as the libraries of the culture.

“One thing I will say is this, the elders back then were uneducated [in a western sense], but they had the cultural knowledge that is rare to find these days.”

For Mr Koro, what started on Tokelau stories about the significance of

songs and dances became much more once he found himself in New Zealand.

There was a divide in the Tokelau Auckland community, and while other Pacific Island countries were all moving forward together, Tokelau’s Auckland community had come to a standstill.

“I see it with my Samoan side, you know if they disagree on something

about the culture, they will fight until they reach some grounds where they can

compromise,” Mr Koro said.

“But what I see with the Tokelau side is like “it’s my way, or no way”

and there’s no middle ground, there’s no compromise…and there’s nothing you can

work with and it’s so sad.”

All Pacific cultures are similar in some ways, some more than others; it

is evident in the flags and pride when Pacific rugby teams play, overwhelming

stadiums with their traditional attire and spirit.

The “red sea” of Tongans who came out in support of the Mate Ma’a Tonga

Rugby League in past years jumps to mind.

It is this spirit that ties all of us together in our unique identity as

islanders from the Pacific.

But Mr Koro says that although Tokelauans are “blessed with New Zealand

Passports”, it is our Pacific neighbours who work hard to live here that are

ahead.

“The Tongans, Samoans and even Tuvaluans they have halls and churches that show for all the hard work they put into their culture and name…and of the 50 or 60 years of Tokelau Mafutaga in Auckland, there is nothing to show of it…”

Picture: Supplied

President for Porirua Matauala Atafu community Lehi Atoni in Porirua,

Wellington, agrees.

In 2013 Mr Atoni helped push for the Inaugural Tokelauan Language Week.

Married with four children Mr Atoni says that while traditional song and dance have an important role, he also hopes his children are learning more from him.

“We don’t have books about our culture, so our history and stories are passed down through oral communications… through stories, songs and dances which is why they are important.”

Mr Atoni talks about his first time here in New Zealand, years ago and how he and other fellow Tokelauans found it hard to speak the language around non-Tokelauans.

He recalls loving his first Easter Tournament, back in 1981; from the

rugby league games to the fatele dances, it united the community in

culture.

He comments that back then, there was not as many Tokelauans as there

are today, so it was just Nukunonu, Fakaofo and Atafu teams.

The events used to come alive with the excitement of seeing families and

friends from around New Zealand all in one place to celebrate together.

It is something that had slowly faded through the years according to Mr

Atoni.

“Nowadays, there are more communities involved, there are church

communities and sometimes we all tend to go our own ways…it’s just not as it

was before.”

He says that the Tokelau community, just like any community, has their

ups and downs, but it doesn’t discourage his commitment to the Tokelau legacy.

Mr Atoni says that Tokelau Language Week “didn’t generate that much

interest in the community” when it started in 2013.

“Now it’s a huge occasion for us across NZ…we haven’t had a census since

2016, and the one before it showed a low number of Tokelauan speakers…but we

look forward to seeing recent data to give us some indication of how far we

have come.”

He and a few others have set up language classes at Matauala Hall in Porirua

and have been working on something to get the language into the NZ Oral

Language Curriculum.

“If Tongans and Samoans can do it, then why not us…we should be at the forefront of it in terms of celebrating our culture and language.”

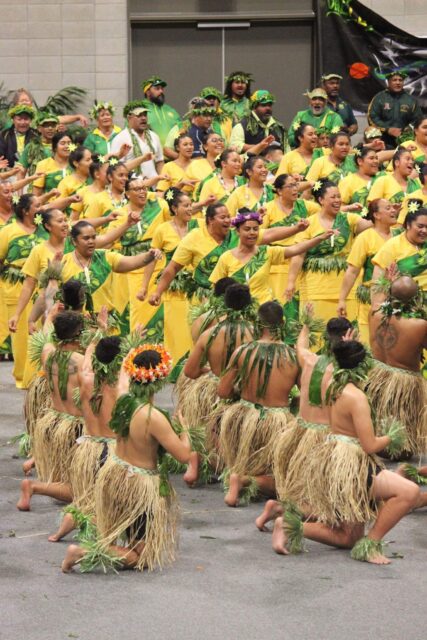

Picture: Lialiai Manea (Facebook)

In a developed country such as New Zealand, it is no surprise that over

the years a few Tokelauans have felt disconnected to their culture.

The Language Week and language classes at Matauala has been a turning point and have resulted in the return of Tokelauans who had felt detached in the past.

But the main highlight for Tokelau’s Language Week according to Mr Atoni

is the last day which holds a traditional fatele to close the event.

Fatele is usually best

performed with a collective group of voices to sing the songs and dance while a

group of men beat the pokihi, a Tokelauan drumming instrument.

Hana Tuisano, who works for the Tokelau Health Department from

Wellington says that there is a beauty in the traditional dances that is hard

to explain.

“There is something in fatele called “matagia” and that’s what makes you Tokelauan, it’s that spiritual unison, the songs and dances all have messages.”

Matagia is a Tokelauan word

that has no literal translation, but its meaning comes along the idea of

bringing the dance alive with joy.

It refers to the pride and excitement of being swept away in the lyrics of the song, of dancing in sync, the beat of the drum, of telling this story that comes in the form of fatele.

-

-

-

-

-

Picture: Fatu Tauafiafi -

Picture: Fatu Tauafiafi

Smiling through video call, Ms. Tuisano whose father is from Fakaofo says

that the Tokelau culture is a community bond and it is why no one dances solo.

“I am that aunty that teaches her nieces and nephews the Tokelauan songs

but when it comes my turn to get into the fatele, you find me watching instead,”

she laughs.

The words of our forefathers who chanted to the seas for fish, sung of the history and danced to honor the legacy, they live on in the fatele or songs and dances of Tokelau.

Back in Auckland, Mr Koro says, in his experience with the Auckland Tokelau communities, they always explained the meanings behind the songs when teaching.

Most of the youth and kids have never set foot on Tokelau and don’t understand the meaning of the fatele, he says.

“So, you explain to them the fishing methods back home are like this, and this fatele is about these traditional ways and why.”

It is a slow but rewarding process, and this knowledge stays with them for as long as they remember the songs and meanings.

Yke Tyoncyo, a Nukunonu radio host in Wellington, says that he finds his

own ways to honor the traditions and cultures of Tokelau.

There is a Tokelauan culture known as kaukumete which is almost

like a graduation, it is a title and responsibility given to boys/men.

The kaukumete is awarded at a certain time that the elders on

island have seen that the boy or man is capable of taking to the oceanside of

the atoll alone to fish.

Men who hadn’t received their kaukumete didn’t have license to fish alone in the oceanside, they had to go with someone who had the kaukumete.

Mr Tyoncyo has three sons who were all gifted a foe, or “paddle”

in English, for their 21st birthdays.

He says that it is his way of giving them the responsibility to take hold of their own destinies in life, mirroring the kaukumete title given back home. Mr Tyoncyo says Tokelau is carried by people who show they are Tokelauan, it is in the songs, it is in the language and the way they carry it is critical for the future generations.

Picture: Facebook

Tui e! Te Ata kua kakau, e laga kita ko te fanau is an old proverb that has survived through songs and

stories of our ancestors.

It is a cry to the old gods of Tokelau from the myths and legends, an inspired call to a nation to move forward, if not for anything else then for the children alone.

Far from home, Tokelauans in New Zealand still hear these cries and it

shows in their maopoopo, in their fatele, in their determination

to keep the language alive.

It is seen in the community’s maopoopo which is how they unite and come together and how they grasp the culture and their teachings to the youth.